NEFDC Keynote: What If GenAI Is a Nothing Burger?

A recent keynote that was a milestone for my own educational journey.

Last week, I hit a personal milestone (actually, several—but more about that in a future post. The one I’m sharing today is about a keynote I got to deliver at the New England Faculty Development Consortium (NEFDC). When I first started in the instructional design and faculty development space in the early 2010s, they were one of two local organizations (NERCOMP—you’re the other!) that I found community, mentorship, and opportunities to share my own work. Since then, they’ve been a community to which I have deeply appreciated for the conversations and communities they have shepherded.

Needless to say, when they asked me to be this year’s keynote, I was surprised, elated, and a lil overwhelmed. It’s something to come into different colleges and universities or conferences that I may never have attended and do this work. It’s not that I care less about them, but in many ways, the stakes feel lower. They feel lower because there’s always a chance of mismatch or missing context that the organizers aren’t telling me. I’m going to do my best but it’s a new crowd—a one-shot opportunity—with strangers whom I may not see again. I might not get it right, but I have to be ok with that or else go down the rabbit hole(s) of doubt and anxiety that won’t allow me to be in the moment when I’m with them (and I think that’s a quality that I bring to these events).

But being in a room with an audience that is probably 20% or more folks I know—past and present colleagues, friends, people whom I’ve been in community with for decades. That feels more risky because more folks know or have some semblance of what I’ve been saying or just my overall disposition about such things. Therefore, I have to craft a message that is both on brand but also offers something new and different than what they may have come across.

Sure enough, I think I delivered on offering something new and distinct. I wanted to make it a little more provocative because I thought it would be the right audience and give me a chance to try it out.

What you read after this, is that keynote—at least as I wrote it—inevitably, there are things I ad lib or realize while I’m talking need more explaining. But this is the primarily the text.

Before reading, I want to note a few things:

This was intentional as a provocation. I don’t know that I fully believe it myself or rather, I go back time and again to the fact that I have lots of mixed feelings about generative AI.

I know the data about the energy usage is not perfectly accurate—but the gist is accurate. Our over-fixation on AI environmental harms comes at the ignoring of systemic energy waste from all the other things we are doing.

I needed more time to make this tighter. I live by the quote (of uncertain origin): “if you want me to give a ten-minute address I must have at least two weeks in which to prepare myself, but if you want me to talk for an hour or more, I am ready.” It was a 1-hour talk but I definitely would have liked more time to refine it.

So enjoy and feel free to leave any comments!

If you want to follow along, I’ve included the corresponding slide number that you can find on this slide deck.

[SLIDE 1]

Welcome folks! I’m really excited to be here as your Keynote. Thank you to Chris and the board for inviting me to speak and thank all of you for joining us here today. Before we get started, I want us all to do something right now to get settled in.

[SLIDE 2]

Spend a few minutes writing down

Imagine 3 years from now–the 5th year of generative AI.

What if this is the actual best we get from generative AI?

What are we going? What will we have learned?

[SLIDE 3]

Thank you for doing that–we’ll return to that momentarily.

Before we get too far into it, I do want to start with a warning. There are parts of this talk that are provocative.

I don’t do this with malice BUT I do it with forethought and hindsight. My intention is not to cause stress or dismiss the struggles that folks have had trying to make sense of GenAI while also all the other demands of working in higher ed.

But let’s proceed. Thank you again for being here. NEFDC has been a special organization for me. When I first stepped into this career, it was one of the first organizations that I found community.

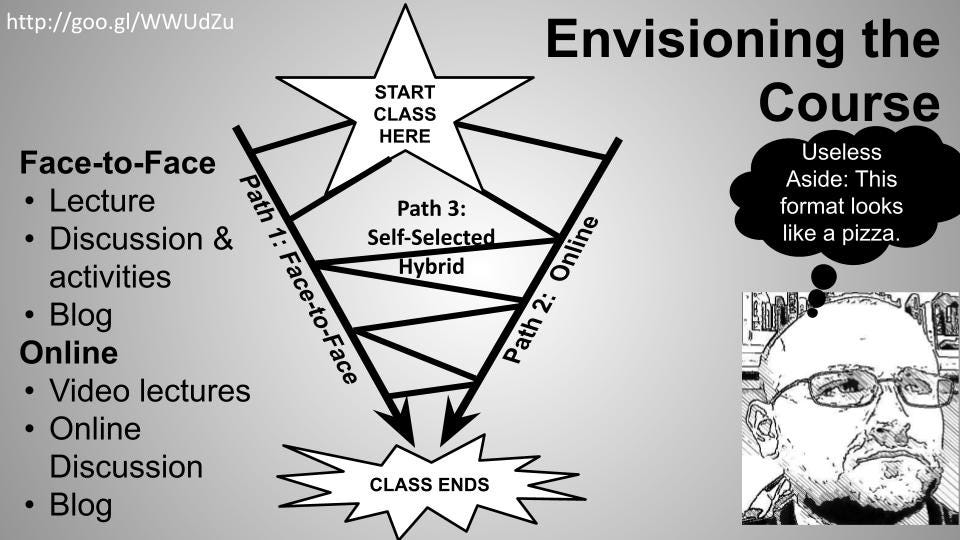

In fact, in 2013, I did a poster presentation on Hybrid Flexible Pedagogy: Engagement by Expansive Choice.

That’s right, I was talking about hybrid flexible learning 7 years before the pandemic.

In fact, I still have the QR code:

[SLIDE 4]

My motivation for leaning into Hybrid Flexible Pedagogy came from students. I taught a class once a week at North Shore Community College.

I had a student who missed class because her life was on fire. She asked me what she could do to make it up and all I could think was–now she’s 2 weeks behind.

Trying to make up when you are behind is really hard in the time-focused structure of education.

For the last 18 years of teaching, I’ve always taught for at least one institution that had a significant population of non-traditional students–whatever we mean by that.

Students who had real life struggle

students whose education was not their sole focus and identity

students who teetered on the edge of believing whether college was for them–often through institutional alienation and indifference.

That led me to wonder about what would happen if there was a way for a student to stay on top of things. That if they missed class, they could still find a way to move forward because life is unpredictable and challenging.

[SLIDE 5]

That led me to create this. A hybrid flexible course that was designed so students could take a course entirely face-to-face, entirely online, or move back and for each week as made sense.

Again, I was designing 2013 and ran it in 2014 and 2015.

QUESTION: Does anyone remember what happened in Winter of 2015 in Massachusetts in particular?

[SLIDE 6]

That’s right snowmageddon struck. From late January until early March we had a blizzard or heavy snow in the first half of the week. This meant that courses that happened on Monday through Wednesday did not meet.

In fact, I had a Monday & Wednesday course. We met on the first Wednesday of the semester in mid-January and then did not meet again until the first week of March.

But my class did not miss a beat. We simply went asynchronous online for several weeks and when it was possible, some of us came back to class.

Other faculty scrambled to figure things out as class after class got canceled and they had to remake their schedule time and again. For all intents and purposes, they were out of luck.

QUESTION: Does anyone remember how they navigated through this mess?

Many of us experienced that and then, also seemed to forget it. Fast forward 5 years and…

[SLIDE 7]

Then, this happened.

The closing of campuses.

The limping to the end of a semester in some mixed bag of synchronous and asynchronous online courses.

We followed this up with a year in which many but not all stumbled their way through hyflex teaching without the real support and guidance that we would need to completely revamp this style of teaching.

Regardless of where you were, you had to be prepared to try and make space for new things–whether in the classroom, on your campus, or in your own rooms from where you were teaching virtually.

[SLIDE 8]

Return to your notes

Capture your thoughts about this:

What is different about your approach to teaching and learning since the pandemic?

What did you do now that you did not do before?

In what ways do you see your teaching different from before?

Anyone want to share out?

[SLIDE 9]

How many are teaching asynchronous courses? What about synchronous courses via zoom or the like? Anyone teaching hybrid courses?

Are you better and more effective, more meaningful, more adaptive instructor now than 5 years ago?

Are you better now because of what you learned and changed during the pandemic?

[SLIDE 10]

What does any of this have to do with AI?

I promise you; we’re getting there. I focus on the pandemic because we’re a few years out from when we stopped really caring about the pandemic, so right now, proves a really good time to consider what happened, what changed, and what didn’t.

That provides us with a sense of what to consider about what we do next and why with AI.

Also,, we can’t talk about where we are with AI if we don’t acknowledge the pandemic as a predecessor. They are both big things that are disruptive and challenging.

But let’s talk about AI–here, I want to share a bit of my own timeline of engaging with it.

[SLIDE 11]

I want to share how I’ve worked through the AI deployment at my institution.

So, November 30, ChatGPT is released.

6 days later, The Atlantic published its now infamous, “The College Essay Is Dead” spotlighting ChatGPT.

Myself and others were beginning to dabble with it and make sense of it

A friend and colleague at College Unbound, Autumm Caines reached out to me believing that one or more of her students might have used it.

We met up and talked through the situation

We both had a moment where we were like, “hot damn, way to go!” for the student–if they did in fact use it. Not even 3 weeks out and someone might be using it–we were amused and impressed.

There was something in that moment that led us to move forward with curiosity.

We decided to survey the students to see if they were using it in her class and then I extended it to the school as a whole.

As the results came in, it was clear that some students were aware of it and were using

it for different reasons such as clarifying language for English language learners or brainstorming ideas for assignments.

I then had an idea and one that felt very in line with both the mission of the college but also my own journey in education that leaned more and more on open education and open pedagogy.

I asked my provost to teach a course on AI & Education for Spring Session 1, which started January 9th.

The goal of the course would be to structure the course around generative AI, learn about it, play with it, consider its value and its problems, and what we should think about it in the higher education context.

THEN we would create a set of usage policies for students and faculty.

We did that in session one and then in session 2, we test-piloted those policies.

Students tried to use generative AI based upon the policies we created with an assignment in a different class.

They wanted to get a sense of whether it worked, was too restrictive, too loose, or if there were unforeseen loop holes.

Faculty were informed of this, yes!

The students reported back and we revised the policy once more.

We handed it over to faculty for feedback and the feedback was useful and clear–nothing extreme or dismissive–largely changes to assure parity of expectations.

Once it was cleared by the faculty, we put it before the Curriculum Committee for approvate and they became our institutional policy.

I’m not saying we’ve solved everything. But we see and feel different about AI as a result of this.

[SLIDE 12]

Now, we’re 4.5 years into the pandemic and we were largely through it–or at least that’s what many decided.

But we’re 2 years into AI and we are just scratching the surface of it. We are still riding the waves of changes.

New things seem to be appearing. Last month, it was Google NotebookLM’s podcast feature; this month it’s ChatGPT’s canvas tool

By the way, if folks have not checked out ChatGPT’s Canvas tool–it goings to be really exciting for some and for others, you’ll probably throw up your arms and resign.

But let’s consider, where we are with this AI stuff and our teaching and learning.

[SLIDE 13]

Let ask this

What is different about your approach to teaching and learning since GenAI?

What did you do now that you did not do before?

In what ways do you see your teaching different from before?

Show of hands:

Has anybody not made any chances?

Has anybody made changes that they feel are positive for how they teach?

(Remember teaching and learning are two different things)

Has anybody made changes that they feel are positive for students' learning?

[SLIDE 14]

What if Generative AI turns out to be a NothingBurger?

So let’s go back to that framing question. What if this is it? What will it mean for teaching and learning? What will be different in 3 years?

The thing is–if we respond with more nuanced and thoughtful assignments, and make sure we become more critical analyzers of information and media–what have we lost?

We will be better for it.

Just like the pandemic–it will push us, it will make us think differently about teaching and learning.

It will force us to challenge our long-held assumptions and will make us see the students in their real contexts–not the contexts we superimpose on them.

That–THAT is key to finding our way forward through all of this.

[SLIDE 15]

I posed this talk as “What if GenAI is a nothingburger?”

And we’ve just explored one side of this question–if it ends up going down the drain–where will we be if we still take it seriously?

That answer is–in a much better space to connect, engage, and guide student learning.

Remember at the start when I said that there was going to be a part of this where I get a bit provocative…well, here were go.

There is another way to read that question–what if GenAI is a nothingburger because the threats or concerns GenAI offers up are not categorically different than what already exists.

We already know the issues.

We have already decided to ignore, acknowledge, or solve for the issues that GenAI brings up…

The real question with GenAI is what if we already know what to do but have to gain the fortitude to do so?

The pandemic surprised us. It caught us off guard. We were shocked in the world at large, but we should not have been shocked in our educational spaces.

Anyone teaching for any duration in the 2000s has seen a wide range of natural disasters close a campus.

Whether it’s hurricanes, massive flooding, raging fires–we should have known this was possible and been prepared for it.

This isn’t a case of hindsight for me–it was a case of foresight and there were others out there too prepared to engage with this challenge.

I’m going to say something and I swear–I swear, I swear, I swear–I am not trying to gaslight y’all. Are you ready? Are you with me?

There is no categorical difference between before and after AI.

There is no existential crisis when it comes to AI.

[SLIDE 16]

AI is a nothingburger.

There is nothing new that AI offers us in terms of challenges or problems that we don’t already have.

Actually, wait, I should define terms, right? So what is a nothingburger?

[SLIDE 17]

Here’s we go!

A term used to describe a situation that received a lot of attention, but upon closer examination, reveals to be of little to no real significance.

That’s from our good ole friend, Wikipedia!

Hey–do any of us remember the Wikipedia Wars of the late 2000s and early 2010s? Anyone still fighting in the Wikipedia wars?

[SLIDE 18]

Anyways, let me ask you, are these the problems that AI represents to us?

I’m going to go down each one–raise your hand if you feel this is an issue of AI?

Credibility/Reliability

Bias

Copyright

Creativity

Ethics of the tool

Equity

Plagiarism

Privacy

Quality

Shortcutting learning and research

One issue missing from this is environmental impacts–but I’ll get to that.

Are there any other items missing that don’t fit reasonably into these categories?

This is a solid list. And yet, the problem with this list is that it isn’t a list I created for AI.

[SLIDE 19]

It’s a list of the concerns and issues that educators had with Wikipedia.

Those are different sources documenting these issues as they relate to Wikipedia:

Like I said, remember the Wikipedia wars.

As Mark Twain supposedly said–I read it on Wikipedia, so I can’t be sure, history doesn’t repeat, but it sure does rhyme.

But wait, this isn’t a list of concerns that I’m sharing about AI OR Wikipedia.

[SLIDE 20]

It’s a list of concerns that educators had with the Internet….

[SLIDE 21]

So again, AI offers us nothing new in terms of challenges or problems.

These are all issues that we have been grappling with–issues that we are challenged by and issues that we feel are somehow different with generative AI.

There can be a bit of a scale of difference here, but it is still the same old problems that higher education grapples with.

[SLIDE 22]

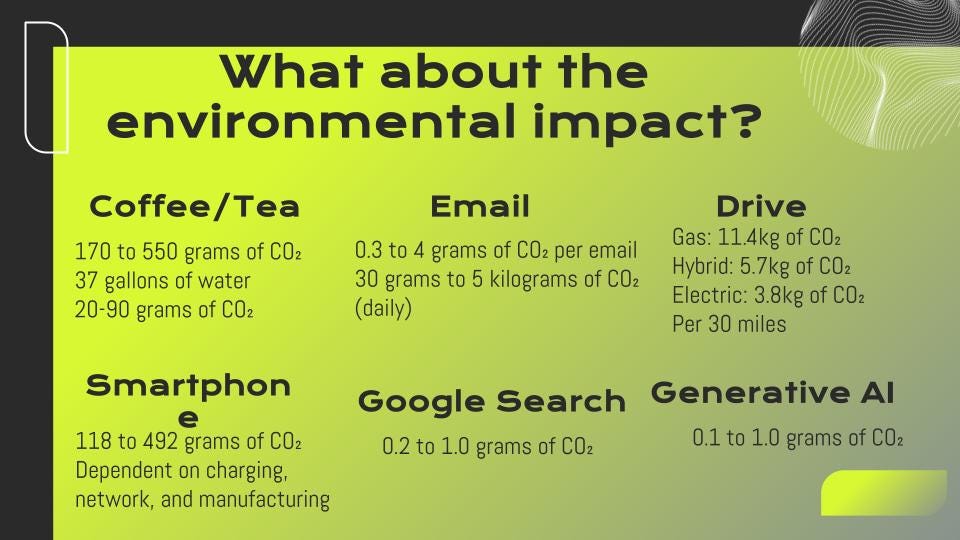

I mentioned the environment too–that there is also concern about the environmental impact of AI!

There’s a young estimation that it is one gram of CO2 put into the atmosphere for every prompt.

I want to acknowledge that. The concern for that is understandable and real.

But let’s find out where we stand with AI and other things we regularly consume in education.

Show of hands–how many people have had a cup of coffee or tea this morning?

How many people have already sent several emails today?

How many folks drove here an have a round trip of 30 miles or more?

How many folks have been using their smartphones

How many people have googled something today? How many people have googled several things today?

Ok–now raise your hand if you ended up raising your hand at least twice during that activity.

Three times?

Four times?

All of these have negative environmental impacts and it’s not just CO2 emissions.

It can take upwards of 37 gallons of water to produce each 8oz cup of coffee. Water that could be used for growing for or just actual drinking.

So I don’t want to dismiss the environmental concerns that generative AI represents and also, it feels like if that’s truly a priority, then we might also be cognizant of all the other things that we’re doing daily that are equally or even more environmentally harmful.

[SLIDE 23]

There’s also something to consider about the environmental costs in that early technology is more wasteful before it's less wasteful. The lightbulb is a prime example but this is true of our cars, TVs, smartphones, computers and more.

Again, this is not to excuse or not be concerned about the environment impact and climate change.

Those are real concerns, but AI itself is not the problem.

It is the whole structure so the hyper-focus on AI comes at the cost of us not questioning the entire system and structure of higher ed.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Bryan Alexander’s book on this particular subject, Universities on Fire.

But still–we feel uncomfortable about generative AI. It really doesn’t sit right. In fact, I found a quote that really sums it up well.

[SLIDE 24]

Let me read you this quote about AI:

“Rather than fostering deep understanding and critical thinking, this tool promotes a passive reliance on external work, leading to a kind of intellectual forgetfulness.

Learners will disengage from the active process of constructing knowledge, placing their trust in external sources rather than developing the internal capacity to think critically and independently.

Instead of empowering learners to cultivate authentic wisdom, this method merely offers them the semblance of knowledge.

It allows them to accumulate information without truly understanding it, perpetuating superficial learning.

This, in turn, risks creating learners who believe they know much but lack the critical depth to meaningfully engage with the world, leading to intellectual arrogance and detachment from true wisdom and transformation.”

How many people feel like this quote captures a good deal of the angst about AI?

Ok–that makes sense.

Except that–you know who said this?

AI said this. In fact, AI said this when I told it to update the following quote:

[SLIDE 25]

“In fact, it will introduce forgetfulness into the soul of those who learn it: they will not practice using their memory because they will put their trust in writing, which is external and depends on signs that belong to others, instead of trying to remember from the inside, completely on their own.

You have not discovered a potion for remembering, but for reminding; you provide your students with the appearance of wisdom, not with its reality.

Your invention will enable them to hear many things without being properly taught, and they will imagine that they have come to know much while for the most part they will know nothing.

And they will be difficult to get along with, since they will merely appear to be wise instead of really being so.”

Any guess what this is about or who said this?

That’s right, our good ole pal Socrates…about writing about 2.5 millennia ago.

Much of our concerns about technology worry us because it is something profoundly different than what came before.

[SLIDE 26]

We live in an age of technopanics.

"A “technopanic” refers to an intense public, political, and academic response to the emergence or use of media or technologies, especially by the young....

a “technopanic” is simply a moral panic centered on societal fears about a particular contemporary technology (or technological method or activity) instead of merely the content flowing over that technology or medium."

I’ve been dealing with them all my life.

Video games were gonna make me violent. I mean Mike Tyson’s Punchout didn’t turn me into a bruiser but it did improve my hand-eye coordination when I started driving.

The Internet did not make me stupider. It made me much more aware of other people’s ideas, pain, and circumstances.

When we’re hit with a technology, there are ways that we get really critical and that can be helpful in this–but also, we sometimes go beyond the pale–we can get too fixated without realizing it.

And, of course, it’s not just AI, Wikipedia, or the Internet, we’ve been worrying about our technology’s impact on us for centuries…

[SLIDE 27]

Television was rotting our brains

Comic books were turning us into juvenile delinquents

The radio was driving us mad

Novels were causing people–particularly women–to have problematic thoughts

It’s enough to wonder if our ancestors made a big mistake in coming down from the trees in the first place.

And, if you recognize that quote, then you’re sure enough to know this one.

[SLIDE 28]

“1. Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

2. Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

3. Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.”

It’s a grounding quote from Douglas Adams. At least, it has been fro me as I crossed the 35 year old threshold a decade ago.

Now, I don’t want to be #3 and honestly, I don’t like the idea of being #2, but #1 doesn’t entice me at all either.

But I do think we have to reconcile with the challenge this presents. The thing is, what this shows me more than anything else is that technology is a perpetual problem; not a solvable problem.

There is no solving technology; there is no technology–it should always be plural–technologies.

And with technologies, there is only an ongoing negotiation and navigation.

And many of the perpetual problems that AI represent, we have yet to solve or address with everything that’s come before.

[SLIDE 29]

Let’s take privacy and security. What do we mean by that and why is that a concern with just AI?

How many people use Canvas for your LMS?

Consider this, Common Sense Media, gave Canvas a 71% rating for its privacy.

[SLIDE 30]

Here are some of the reasons why.

Don’t worry, blackboard didn’t do much better.

[SLIDE 31]

They got a 75%, or a C, which means they could transfer that grade, right?

And for those with Brightspace, you got a 76%.

Again, we should be concerned about the privacy issues, but the LMS is just 1 tool among dozens that has vast amounts of information about us and our students swirling around, often without our understanding of what’s being done with it.

[SLIDE 32]

Coypright is another great example of this.

There are real concerns about copyright with AI.

But also, why are we so quick to uncritically accept that copyright is actually working well.

It’s 2024 and you know whose works are still locked behind paywalls? Much of the work of people from the mid-20th century such as John Steinbeck, Albert Einstein, James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberryso many more.

Why do we think that works should be locked behind paywalls for 70 years after the death of the author–how is that actually conducive to the production of knowledge?

I’m all for protecting authors and their creativity, yet this system does not actually serve them–it’s been broken for a long while now.

[SLIDE 33]

But this is what I mean–I could go through each of the issues that we brought up around AI–and each of them already exists.

Each of them, we are already systematically ignoring or are finding ways to figure out.

I don’t want folks to believe I’m saying that these aren’t problems.

But these aren’t problems with AI–these are perpetual problems with technologies. Some we figure out in due time; others we tolerate, and still others, we ignore.

It’s only when a pandemic or a quickly deployed technology arrives–OR BOTH– that it shell-shocks us enough to feel like we’re scrambling.

Having these two back to back has meant we’ve felt the compound interest from these problems to negotiate. We were hit hard and haven’t been able to catch our breath.

[SLIDE 34]

So, let’s actually take a breath. Collectively.

Everyone on the count of 3. We’re going take a deep breath, hold it, and release–together.

One…two…three.

OK, I know that didn’t solve anything but I also know I just spent the last chunk of this talk telling you something that many of you may not believe.

And maybe right now, you’re feeling a little bit like Bear [NEXT]

or maybe a little bit like Pumpkin [NEXT] …or both.

Cause now the question is–what does this mean?

We still have to go back to our faculty or students, and find a way to help them through this.

Let’s see if we can find our way there in the time we have left?

[SLIDE 35]

Return to those notes.

Capture your answer to this:

What makes you great at your work?

What is the thing or things that you bring to work that make it YOUR work?

[WAIT 1 minute]

Ok–now, turn to a fellow attendee and brag for 1 minute about yourself. Seriously.

Determine who is going to go first.

Tell them what makes you great at work.

And after a minute, I’ll have you switch.

Now, pay attention–really listen to what your partner says because I’m going to ask about it after.

SWITCH

Ok, what did we learn?

Can someone share what is awesome about the person they talked with?

Show of hands–how many people identified one or more aspects of what was just shared?

Let’s take another one.

[SLIDE 36]

Maybe we’re starting to see a pattern, yes? We all are doing deeply meaningful, relational, connective work.

We bring care, forethought, and passion to our work. We often operate both as a shield of protection for faculty from administrative BS and also as a cultivator and curator of faculty excellence if we work in educational support

And if we’re faculty, we try to convey the meaning, importance, and deep value of our disciplines to our students with a recognition of who they are.

In the end, what we all bring to this space is the desire to make teaching and learning better.

And I know it’s corny as hell but THAT is what is going to help us.

I wanna bring attention back to my friend, colleague, and collaborator and all around wonderful human being, Autumm Caines–yes, I spelled it right on the slide. She wrote a post a over a year ago, called “Looking for ChatGPT Teaching Advice? Good Pedagogy is Nothing New”.

And the headline says it all. But be sure to go read it.

We already know what good pedagogy is.

What we need is the fortitude, the self-confidence, and the trust-building amongst ourselves and with our students to do it.

Because good pedagogy is not a checklist. It is not a set of best-practices that you can look to and easily enact.

[SLIDE 37]

Good pedagogy takes time

Good pedagogy is contextual.

Good pedagogy is messy.

Good pedagogy is emergent.

Good pedagogy is relational.

Good pedagogy is personal.

Good pedagogy is political.

Good pedagogy is transformational for student & educator.

Good pedagogy is the thing that AI cannot replace.

So what does this mean for how we go forward? What does this mean for how we think about and support our students and faculty?

[SLIDE 38]

We can’t dismiss those that are dismissing AI

We just can’t. I’ve been working in instructional design for 13 years, I’ve been working with faculty around teaching and learning for more than 16 years. ]

The people I have learned the most from are the people that are skeptical, hesitant, and outright resistant. We need them.

They will be important in this ongoing discussion. It doesn’t mean that we have to accept everything they say but we need everyone in the room.

[SLIDE 39]

We should be skeptical and hesitant–that’s our jobs

Yes, we should. I say this in every talk and nearly 2 years in, it is still true–with AI, with every technology.

I’m not here talking to you because I’m trying to say let’s all go full steam ahead with AI. I’m like Heinz 57. I have 57 different opinions about the place of AI in our society and education every single day.

We need our skepticism and hesitation, even when we’re excited about it. That skepticism is going to help us figure out what is real, what is technobabble silliness, and what is best for our institutions.

[SLIDE 40]

We need imagination, not just skepticism.

Even if we have skepticism, it should not keep us from engaging with AI and learning more, understanding how it relates to our work, our teaching, our learning.

We also need to imagine–to see what AI might be or could be in our disciplines in positive and neutral ways.

Just like we tell our students many of the lessons of our disciplines that they can’t learn it from a book.

I mean I teach literature and it’s even true there–it requires more than just reading, it requires immersion.

We have to do some immersion into AI.

We have to explore and simulate a world in which these tools are permanent and change how we approach our subjects and teaching.

And we can’t just do it with skepticism; we need imagination and curiosity.

[SLIDE 41]

Yes, we’re still better by engaging with it–that’s learning

So bring that skepticism and that imagination.

Don’t let our skepticism keep us from learning what does and doesn’t work. What’s useful and what’s not.

Lean into that learning–is it uncomfortable and concerning? Sure–but honestly, in doing it, you’re also building some deeper understanding of students and how they struggle in our courses–particularly the ones they don’t want to take or the ones they think hold no value to them.

What can you learn by leaning into uncomfortable things, new things, uninteresting things, scary things that can help you be a better educator?

[SLIDE 42]

We should understand AI well enough to guide students

Ultimatley, we need 2 buckets.

The first bucket is our disciplinary knowledge. The deep well of understanding we’ve honed over years.

The second bucket is a strong understanding of how GenAI works.

We need both of those in order to help our students figure out the right roles of AI. And to be clear–that is a moving target. That’s why it’s scary and hard–because things keep changing. Again, technologies are a perpetual problem, not a solvable one.

[SLIDE 43]

Finally, to those folks that are resistant here or ones back at their campus. The question to ask and consider is this:

What if you are wrong? What if AI turns out to be incredibly important for your students? What then? How will that impact your classes and your students' growth?

What is lost in your courses as a result? What are your students able to do in a world where AI is ubiquitous and expected?

[SLIDE 44]

Because if we’re critically engaging with generative AI–we’re recognizing its affordances, wary of its problems and harms–and recrafting our teaching and learning to move towards more process-focus activities and other forms of assessment that feel more authentic, get more nuanced, allow for more creativity–then we’re still better for it.

Our students are still going to be better for it because we’re changing and adapting our pedagogy. We’re responding to the students in front of us in the world they currently live in and have to navigate through.

We’re taking their agency seriously by not pretending these tools don’t exist or there is no actual value to them.

That is powerful and transformative.

Of course, it’s not easy, but it’s also not impossible.

It’s part of what teaching in the modern world requires–to grapple with technologies, to build relationships, and create learning experiences that students can see themselves a part of.

Teaching and learning is dynamic and while we don’t have to love or irresponsibly deploy AI, we do need to learn about it, share it with our colleagues, and engage with our students about how it's likely to impact all of our disciplines.

[SLIDE 45]

Again, when we engage with this thing we’re calling AI–we’re not actually grappling with AI–we’re grappling with a perpetual problem that literally goes all the way back thousands of years in education!

We don’t have to like it; we don’t have to embrace it; but we do have to use our skepticism and our imagination to understand it and make sense of it for and with our students.

To me–that’s education in a nutshell–regardless of topic, modality, or technology.

AI+Edu=Simplified by Lance Eaton is licensed under Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Standing ovation. Brilliant, brilliant talk, Lance. I will be sharing this with our faculty through my weekly edtech news feed. Bravo!

I don’t think gen AI is comparable to Wikipedia at all. Wikipedia has human editors, checks and balances etc (or at least is has evolved into having). It doesn’t tell you to mix glue into pizza sauce like Google’s AI did the other day. As far as ethics go, Wiki is way further ahead. The problem with AI is that its barons don’t seem to really care about checks and balances, like Jimmy Wales did. It’s NOT technophobia, it’s fear of the insanely rich and irresponsible human beings in Silicon Valley who only care about their own profit, as we have seen with Zuckerberg, Musk and the like for the past two decades.