Ctrl+Alt+Assess: Rebooting Learning for the GenAI Era

In April, I had the honor to be a keynote for Advancing a Massachusetts Culture of Assessment (AMCOA); a great organization that has some of the people I deeply respect and have had the opportunity to work with over the years. As it has been a bit of a different approach to some of my other talks, I figured I’d share it here for folks to dig into.

I’m super excited to be here, folks.

Let's start with an activity,?

Is there anything that you're passionate about? An activity that you just really, really enjoy doing? Raise your hands.

All right, keep them up.

Now, are you good at it? Keep your hand up if you feel like, "Yeah, I'm good at it." I see some hands going a little bit lower.

We can be passionate about stuff we are not good at. Trust me, I’m passionate about a bunch of stuff I’m not good at.

And finally, let’s find out: how do you know you’re good at it? Anybody want to share what they're passionate about, and maybe share how they know?

One of the things we’re thinking about in education is: how do we come to know if we're good at something? We do so either through our own internal effort to deeply understand what we're doing or through external validation.

External validation can come in many forms. We sometimes talk about external validation as doing it "for the likes," but there are other important ways that external validation matters, not just superficial ones. I want my doctors to be externally validated, right? We want those things.

And so, for education, when we think about how we determine if students are good at things, we’ve over-relied on some methods and shied away from others. We've privileged that which can be mass-produced; those that are easy to create, share, grade, and return. Things like tests and writing were those quick and easy things.

I know we don't think of grading writing as quick and easy, but compared to other types of assessment, it is. It comes in a standardized bucket, be that paper or a digital document. It was the easiest to share out and quickly assess, relatively speaking. But it isn’t often the best way to determine if learning has occurred if the thing we want them to do in the actual context is the thing that they can do not just write about.

This makes sense within the U.S. context and a history, which often focused on tangible, quantifiable output and privileged that over process. We are very much a hyperproductive society. Or rather we are hyper fixated on productivity.

One challenge within education, and higher ed in particular. is that we steer two behemoths of what higher education is. On one hand, we're here to support the intellectual development of students, to help them develop their inner lives and their civically present lives. Education that pushes them to look inside their souls and to truly understand what it means to lead a meaningful life, a life that is connected with other humans in society.

Yet we're also here to prepare students to do the work they're going to do in their lives. It’s impossible for most people not to have some kind of work. Whether that's running a business, leading an organization, or experimenting in a lab; it’s all needed. We need both of these missions.

So, how can we demonstrate that students are capable of both of these when they graduate? It’s getting really mucked up. I don't think we were ever that great at it, but it's getting particularly messy now…because of this guy.

Who knew? Who knew the pain-in-the-ass that was Clippy would sire a great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandchild known as AI? And one that feels more like a mix of Sheldon Cooper and Ned Flanders than HAL 9000 or Skynet, right? That’s where we are with AI right now.

We are in this age of AI, and it reflects a bigger challenge we’re going to need to reconcile if we're going to articulate the true value of education as a form of individual, social, communal, and interpersonal development.

Given all the changes and challenges just in the last year, it feels like one more thing. But it is an important thing. And I don’t want to bury the lead but there is no magic bullet. There's nothing I'm going to say here that's like, “Perfect! I can go back to my campus and get on with my life.” There’s no perfect solutions for GenAI. This is going to be complicated. It’s going to be challenging.

I hope that through some of the things I talk about here that there will be some new ideas you take away, some things that ruffle your feathers, possibly, and some things that make you wonder, “Maybe I need a different set of tools to figure this out.”

Also, I think it is incredibly important that the answer for us is not better mousetraps.

I know there's a real concern about what AI allows students to do, and we know there’s some small portion of students who may always cheat the system. But trying to catch them isn’t the real answer. The bigger issue is the big middle, where AI is seductive. It allows for people who are already overtaxed, just like all of us, to use it as a path of least resistance. It is seductive.

But we can’t treat their use of AI like it’s a trap. We can’t be like, “Aha! Gotcha!”.

It’s been a lot. We’ve all been navigating a lot of different things.

There’s a lot going on at the national level but much of it has been going on for years. What were once hints or threats are now becoming real harms that we’ll have to increasingly navigate.

And I can’t talk about AI without also recognizing the pandemic. There was a pandemic. And so many faculty, while maybe not doing things perfectly, completely transformed in just a few short weeks.

Yet just as we were kind of coming back to whatever we want to pretend normal is, we end up with AI.

It’s not easy. Educators everywhere have had to carry so much. Lots more is being asked of them. So much more they have to think about.

There are faculty who are deeply caring. Faculty who have been working for twenty years to perfect their practice. And they see it as a practice. They keep showing up. They keep doing the things that are asked of them and updating their practices.

They’ve been listening to their instructional designers, their faculty developers, their assessment folks. They’ve been working on alignment. They’re putting together their outcomes and they’re actually good outcomes. There’s not an “understand” to be found anywhere. They’re coming up with meaningful and useful assessments, and then developing the learning materials that help get students there.

When you do that really well, you develop a very rich, interconnected web.

The problem is that generative AI came in and just did that thing we all do with cobwebs: we sweep it all away. Just scatter it. And that’s really hard because that’s a part of what happened in the pandemic, too.

Now, it’s happening again, except trying to figure out the process, trying to figure out how to rebuild that web, is hard. It’s frustrating and depleting when you've been doing it. You thought you got there, and then all of a sudden, it's not just one thing, it becomes everything in there.

Navigating Technological Shifts

Anytime I’m feeling confused, befuddled, frustrated, or off balance about technology, I turn to Douglas Adams. This is my second favorite quote of his:

“1. Anything that is in the world when you're born is normal and ordinary and just a natural part of the way the world works.

2. Anything that's invented between when you're 15 and 35 is new and exciting and revolutionary, and you can probably get a career in it.

3. Anything invented after you're 35 is against the natural order of things.”

I hear way too many affirmations right now!

But regardless of our age or disposition, if you're in assessment, you're going to need to create careers in and around AI. That’s something I think we’re going to have to reconcile. If you're working in assessment and haven’t started to play around with or think about AI or just tried to get a better grasp of it, I think you’re going to have to, and quickly.

Now, I'm not up here as an AI cheerleader. You'll see throughout in this talk there are points where I’m just like, “AI can be really... meh.” But we do need to think through the ubiquity of this tool.

Higher education needs the assessment community to help us figure this out. Faculty are struggling, frustrated, and exhausted. They need help and guidance. Especially in the face of a tool that can help students bypass their learning.

And again, I don’t want us to think about that maliciously. There’s something incredibly seductive and also helpful about these tools and what they allow people to do that they might not have felt capable of otherwise.

The thing is, AI isn’t even that good. I mean, it's interesting. It can do some cool things, but it’s also incredibly inept.

Here’s Exhibit A or maybe I should call it “Exhibit AI.” The amount of times it took me to get the AI image generator to fix this text was embarrassing. I swear, it was gaslighting me or just mocking me.

There are just things it cannot do well.

If image creation still feels like magic to you, how about table alignment? I spent four or five prompts with an AI trying to fix a table it made. I said, “Hey, just top-align it.”

Four or five prompts, waiting for it to come back, and it responded: “It’s table-aligned.” I’m like, “No, I can see it. It’s not right.”

What is that?

Something I could have just copied and pasted into Google Docs or whatever and done myself, it couldn’t figure it out. And I think this is important. This is the challenge. This is why it’s easy to dismiss AI. This is why we can say, “Ah, it’s dubious. It’s limited.”

But also, it can do things. And so, we’re caught in the chaos.

It all feels very chaotic. And also very fragile. Swinging back and forth between“I don’t have to worry about it” or “I completely have to worry about it.”

And we’re stuck in that middle space—that liminal space. That great gray area that we’re never really good at navigating.

But I do have hope. And when I say hope, I mean hope like the way Caitlin Seda says it: hope that is tenacious, that is determined, that is fierce. It’s one of my favorite poems about hope. It’s a great callout to Emily Dickinson.

I do believe that even though it’s going to be hard and complicated, we’re going to figure it out.

I’m going to ask us to do something right now is because I want to explain why I have hope.

You can write this down, or you can just do it as a thought experiment.

I want you to imagine that on Monday, you go back to your campus. You go back to your courses. And imagine that you, your students, your institution, your colleagues—none of you have access to any digital technology.

Somebody just gasped. I think someone had a heart attack!

But seriously, think about this.

Can you still actually and literally function? Can you do your work? Can you teach your courses?

I’m going to give you about a minute or two to play this thought experiment out.

And I want you to remember: we’re going from today, which, let’s be honest, probably has a digital device–to–person ratio of 2:1 in this room, at least. I’m going to guess that’s the minimum, just in this row.

Think about that. We’re going from that... to none.

People are pulling out their watches, like, “Oh gosh, I’m already the Borg.”

So just give yourself a minute. I’ll give you about 60 seconds.

So, show of hands, how many people, going back on Monday, would actually be able to get work done?

This means all your work is on physical paper. All of your contacts are written out and accessible on landline phones. Right? How many of you are still using landlines?

Are your materials digital at all? Are your notes digital or physical? Your tools for analysis; are you mathing those out by hand?

The reality is, it would be incredibly hard for us to do that.

So why do I think that’s hopeful?

(Some people are like, “I don’t know, I’m just still breathing from the idea of it all going away.”)

But we’ve already learned how to integrate technology into our work to a deep degree. This is just one more element.

This chart gives me hope, because it reflects all of the different digital technologies that we’ve already integrated into higher ed. Many of them have become fairly common—maybe not universal, but widespread.

So, let’s do a little walk down memory lane:

We’ve got the card catalogs. The chalkboard. The good old pocket calculator.

Then we moved to the scientific calculator. Spreadsheets—those were so exciting, right?

Word processors. Databases. Laptop computers! We’re getting into the '90s now.

Voicemail systems: the thing we all send our calls to now because no one actually answers their phone anymore. We’re all guilty of that.

Then came e-portfolios. External hard drives. Learning Management Systems. Social media platforms. Wikis.

Now we’re into the 2010s and 2020s.

All of this technology.

There’s so much that we’ve already encountered. And let me just say: if you’re feeling exhausted, that list might be why.

We’ve integrated all of that and are still sitting with it today. That’s a lot. But that’s also what gives me hope: there are so many things we’ve drawn on, so many tools we’ve adapted to, and so many challenges we’ve navigated.

Here’s another quote that resonates in these moments. It’s almost the same quote from Peter Pan and Battlestar Galactica—obviously the 2004 version:

“All of this has happened before. All of this will happen again.”

That’s where I get my hope from.

We don’t just have a playbook; we have many playbooks on how to navigate what comes next. And yes, AI feels new and different in many ways. But so did all of those technologies when they first emerged. And we figured out where they worked, and where they didn’t.

So, we may not know exactly what must be done, but we know we can do it—because we’ve been doing it.

We have lots of things to draw on: lessons, strategies, wisdom.

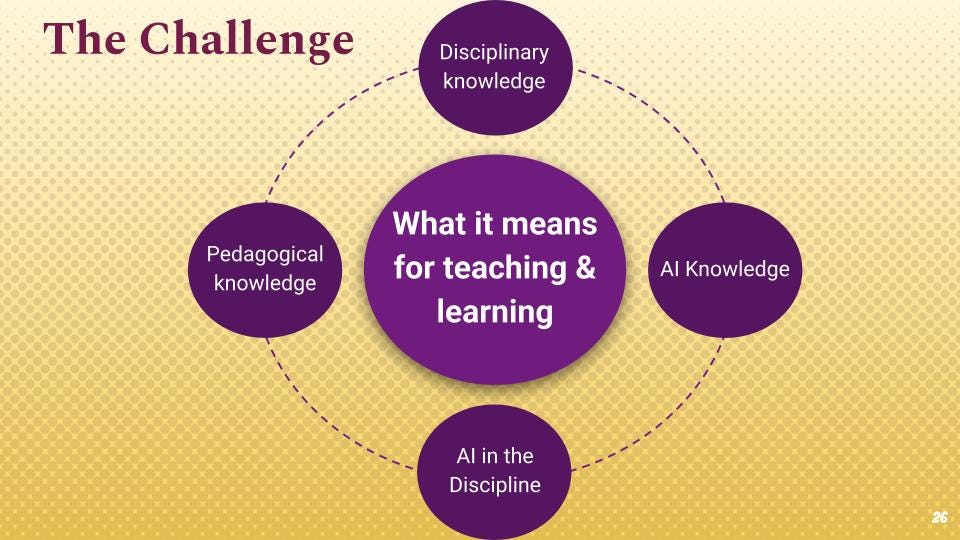

The Challenge

This is the core challenge that educators are facing in the classroom right now. And this is where assessment work becomes incredibly invaluable.

This challenge has four smaller and interconnected challenges:

Disciplinary knowledge: The heart of what people go to college for. Knowing and doing within a major. What does it mean to be a chemistry major? A historian? A sociologist?

AI knowledge: Everybody in education is going to need to know something about AI. Just like we all had to learn the internet, or how email works. At one point, you really had to understand ink, quills, and paper. Now, it’s AI: its capabilities, its limitations, and the temptations it presents for bypassing learning.

AI in the discipline: How is AI showing up and changing the field itself? We just discussed how many of you, people with advanced degrees, said, “I can’t do my job without these tools.”

That matters. We know digital technology changed every discipline. You can’t be in many fields today without that knowledge. So, how does AI now reshape those disciplines?

Pedagogical knowledge: Taking all of that together: what does the discipline mean in the age of AI? How does AI show up in how we teach? What do we teach? What don’t we teach anymore? What do students no longer need to prove they can do?

These are hard questions.

I’m of a certain age. I started writing by hand and I’m left-handed. My handwriting was terrible. It shaped my academic trajectory.

There was a clear moment in middle school when my grades improved. That moment was when my teachers realized I had a computer and allows me to type my work. Suddenly, my thoughts were neat and legible. I wasn’t worried about smudging or legibility.

People still argue for teaching cursive; I get it and I’m also like: get rid of it. For me, it didn’t serve my learning. It held me back.

All four of these challenges, we’re trying to figure out all at once. That’s the hard part. Other technologies took 10–15 years to fully integrate into our work. But faculty are having to figure this all out now, all at once.

And that leads me to one of my strongest book recommendations. In fact, I just finished it over the weekend. (Scratch that—I listened to it. I’m a huge audiobook nerd.)

To date, I’ve read over 100 books about AI. And this one is my go-to for anyone in teaching and learning, anyone in higher ed who’s asking, “What do we do?”

It’s Matt Beane’s The Skill Code. (I’m sure someone’s Amazon account just went ding-ding-ding.)

What I really like about Beane is that he recognizes the core problem we’re all concerned about: how do you become knowledgeable and expert in a world where AI or other technologies do all the heavy lifting of thinking and development?

There’s currently no good system to guide and support learners through their zones of proximal development. You don’t necessarily get the deep, real practice that’s needed. And because of structures of learning, learners and early-career folks don’t always get to develop expertise in meaningful, situated ways.

Beane’s framework focuses on challenge, complexity, and connection as the foundations of skill development. He offers a critical lens for rethinking assessment practices, especially as AI tools like ChatGPT transform academic and professional work.

Traditional assessments, as we know, often measure discrete knowledge rather than authentic skills. That’s how it’s often been: measuring what can be easily checked off rather than what learners actually need to thrive in the world. Beane shows how technology can either undermine or enhance skill development but we have to reconsider what assessment can look like and how we do it.

He offers a thoughtful roadmap for designing assessments that preserve the essential human elements of learning while leveraging technologies as partners, not replacements.

And the one of the most valuable considerations for assessment from this book is his idea of chimeric approaches. You may have heard similar ideas described elsewhere like the “cybernetic centaur” from Ethan Mollick but I like how Beane lays it out in terms of where human and technological capabilities are integrated and mutually supportive.

This informs assessment design that intentionally incorporates AI, because we’re in a world where nearly all of our assignments are digital. Yes, we still have some live formats like presentations but even those are often digitized, whether they’re happening asynchronously or over Zoom. So the digital layer is already embedded in much of our assessment. And AI likely is too. That’s the lens we need to use to start rethinking what this can look like.

Now, if you know me, you know: these are great big ideas. They’re thoughtful and interesting. Yet if I leave without saying, “Here are some things you can try,” I haven’t done my job.

One is the resource document. But I want to walk through a few assignment and assessment ideas that will be you to take back with you, especially if you haven’t already tried them or need some ideas to support faculty figuring out this work. These have been examples that faculty can build from together.

For those critically inclined to side-eye everything AI, red-teaming is your friend.

This means helping faculty understand that if you want students to think critically about AI, then actually have them think critically about AI.

Red-teaming involves adversarial thinking, engaging with AI as a system to challenge, interrogate, and analyze. It could be the instructor prompting adversarial scenarios. It could be students doing the critique. It could even be AI-generated content out in the wild that gets taken apart.

One really effective method, adapted from Maha Bali, is starting with visuals before moving to text. Students are generally better at analyzing visuals; they notice inconsistencies, absurdities, and patterns quickly. (Hence our many insecurities—humans are good at visual critique.)

Visual critique becomes a great jumping-off point for deeper analysis. I’ve also seen faculty use this approach with tools like NotebookLM, especially its podcast feature, asking students to critique the dialogue, explore gender dynamics between male and female hosts, and uncover implicit bias.

There are many ways to do AI-critical assignments that are rich in substance and aligned with learning goals: critical analysis, argumentation, bias detection, ethical reasoning.

These are the things we’re already asking students to do. AI becomes the object of critique, not just the tool to use, which makes it a dynamic source in teaching critical thinking, not a threat to it.

One powerful approach is having students create something with generative AI but then requiring them to objectively, outside of the AI, prove that everything in the product is accurate. And where it’s not accurate, they have to identify that and explain it.

This quickly reveals how many things are unclear or misleading in AI-generated content. And so, again, students get into finding evidence, developing arguments. The goal here is: if you want to use AI, fine but I want you to understand its limitations. I want you to know how to play with it, how to critique it, and most importantly, how to build your own disciplinary knowledge that isn’t tied to a tool that will just spit out a blend of plausible-sounding but unverified answers.

Another strong and highly engaging strategy, one that many faculty are drawn to, is using AI to create simulations. This allows students to walk through processes, procedures, or types of practice across a wide range of disciplines. There are obvious applications in fields like business or law, but really, you can design simulations for almost any discipline.

Even in writing instruction: have students coach a fictional peer with poor writing skills. How do they guide them? How do they offer meaningful critique?

We talk a lot about how we learn by doing—or by teaching. AI gives us a safe, low-stakes space to do that. There’s no judgment. There’s a lot of flexibility. And it’s an opportunity for repeated practice.

One of the best uses I’ve seen is when AI is paired with reflection. Reflection is a powerful force in learning. It builds metacognition. It connects ideas. It activates the brain in rich and meaningful ways.

There’s incredible opportunity in this to deepen student thinking and improve reflective practice. And honestly, while I love reflection and always use it in class, I often wish my students could go farther. AI offers a way to do that.

The challenge with traditional reflection, as I’ve seen in my 20 years of working with students, is this: you assign a reflection, give some guidance, students submit it, and then, ideally, within a week, you return feedback. The proccess is too prolonged and often, you’re reading a reflection and thinking, “Oh, I wish I could ask them this,” or “What didn’t they like?” but the window for that deeper digging has already passed.

Now imagine reflection as an iterative conversation where the AI is deeply curious about the student.

It keeps asking questions:

“What didn’t you like about that?”

“What was the problem you encountered?”

“When you say X, what do you mean?”

“Can you give me an example?”

Even the format of reflection changes: instead of staring at a blank Google Doc and typing something abstract, students talk to the AI and submit the transcript.

Now this next one; this one is my dream. It’s completely abstract. I haven’t seen it implemented yet, but I think it’s where higher ed needs to go.

It’s the idea of building a course, or even just a unit within a course, entirely around the question: “What are the skills, knowledge, and abilities that now define this discipline in the age of AI?”

That becomes the focus of the course itself. And students co-develop that inquiry with the instructor.

There are lots of ways to do this:

As an ongoing conversation throughout the course.

As a design lab: reserve time and space to test ideas, build workflows, and analyze disciplinary changes.

As an assignment: have students map how AI is transforming their field and what that means for their own preparation.

This is where my own background really kicks in because this is the kind of co-constructed, inquiry-based, purpose-driven learning that gets me excited. It’s about bringing students into the process. It’s about figuring it out together.

This is partly inspired by what I ended up doing at College Unbound in January 2023. At that point, ChatGPT was only about a month old. And yet, I ran a course on AI in education. The whole point was: “Let’s figure it out. Let’s see what this can do and what we can understand about its implications for education.”

Through that course, we created a usage policy for both faculty and students at the institution. We ran the course once, it went really well, and we came up with a decent set of recommendations. Since courses at College Unbound are eight weeks long, I was able to run two in a semester.

In the second course, we test-piloted the policies. That meant students took the drafted guidelines and applied them in other classes. (To be clear, we informed the faculty in advance; we didn’t just surprise them.) Students tried out the policies in real classroom settings. Did they work? Did they feel appropriate? Were they too rigid? Too vague?

We put the policies in front of faculty for feedback. And, as they should, faculty had comments. But they were useful. Most focused on clarifying language or establishing parity, like, “You say students are responsible for X, but are faculty responsible for Y?” That kind of detail.

It was a powerful process, and eventually, those policies became the institutional guidelines.

As we think about applied learning; learning that feels meaningful. This definitely dovetails with service learning and civic engagement. These tools allow students to do things that have real-world impact. And we know that’s a huge goal of service learning: asking where what students do in the classroom intersects with the world. These tools create really powerful opportunities for that.

A Few Guiding Considerations

As we close, these are a few core ideas I often want folks to keep in mind:

Abstinence has never been a great strategy. It didn’t work during Prohibition. It didn’t work in the War on Drugs. (The drugs won.) It didn’t work in abstinence-only sex education. Avoidance is not a strategy. We need to learn about AI. We need to engage with it, experiment with it, and integrate it; yes, in our classes. Simply banning or dismissing it won’t work.

All that will do is further make higher education feel irrelevant, especially in a cultural moment where that critique is already made, repeatedly.

Now, this doesn’t mean we can’t have guardrails. We can. We absolutely should. But those guardrails need to be communicated clearly. We have to explain why they’re there. And we need to help students understand that some friction is necessary in learning. But we cannot avoid this technology. We shouldn’t.

This is especially important for folks who are wholly dismissive of AI, whether in this room or back on your campuses. There are valid reasons to be skeptical. I get it. Driving here today, I had about 15 different feelings about AI. That’s my everyday. I work in this space, and I’m still torn on the good, bad, everything in between.

But if you’re someone who says “absolutely not,” I challenge you: find just one use case of generative AI that makes you go, “Ohhh.” That doesn’t mean you have to keep using it. It doesn’t mean you have to embrace it. But you have to understand why this technology is transformative for some people.

This isn’t about gimmicks. This is about people finding tools that work for them. And if we, as educators, don’t recognize that—if we dismiss it outright—we will alienate our students. We will tell them, directly or indirectly, that something meaningful to them is “a fraud.” And what happens when someone tells you something deeply meaningful is “a fraud”? They lose your trust. That’s what we risk. And that’s why this matters.

And finally, none of us are going to figure this out on our own. We need to figure this out together. Each of us brings different pieces to this. This is a big challenge. It’s also a big opportunity. It’s a significant moment in education.

To me, it’s bigger than the pandemic because it reshapes not just a delivery model or a semester, but the very web of learning, knowledge, and assessment. It forces us to rethink everything connected to that web. And we need everybody for this. We’re going to need our collective wisdom. We’re going to need everything we’ve learned from all the digital technologies we’ve managed to integrate into our lives.

It’s here. And it’s going to continue to challenge us. It’s going to change. And it shouldn’t fall on the shoulders of one person, or one office. That’s the key message we need to bring back to our campuses: this work is not just for faculty to carry alone. That’s a mindset institutions haven’t fully broken out of yet.

I’ve been working in higher ed for decades now and what continues to inspire me are rooms like this. Being in a space filled with brilliant people. Some of you I’ve known for years. Some of you gave me my first opportunities to step into this work. And honestly, if we’re going to challenge, reconfigure, and reimagine higher ed, these are the people I want to do it with. There’s so much wisdom here. There’s so much care. And that’s the key: it’s not just about figuring out the problem. It’s about doing it in a way that supports our students and supports our faculty.

So I’ll end with this: Once again, I’d be remiss if I didn’t show you the clunkiness of AI because this is what I finally ended up with.

I tried to get ChatGPT to generate this image from the Uncle Sam poster reimagined with a robot princess. But no, ChatGPT was not having it. It responded, “This request violates our content policies.”

So I tried to reassure it: “No, it doesn’t violate policy!” Still nothing.

Then I did the classic “well, actually...” and made a fair use argument. Still no. Still not buying it.

“I understand the concept of fair use,” it told me. “But I operate under stricter guidelines that prevent me from generating content that references certain things.”

Okay, fine. So I said, “Design a robot princess holding a sign with this particular message.” And that, finally, it was willing to do.

This is where we are.

We’re in a space where we know this technology is going to change. We know it has limitations. We know it’s both amazing and frustrating. It may not do the same thing twice. But we need to figure it out and we need to figure it out with faculty.

And for me? It’s not that I want to live in interesting times; we’ve been living in interesting times. Still, I do think this is an exciting challenge. Because truly, when else in education have we been at the start of something that’s got this much potential to fundamentally reshape the work we do? And in this room, I saw so many smiles, handshakes, hugs; so many people here have known one another as colleagues for years, or even decades. This is who we get to figure this out with. And that, to me, is something really powerful. Thank you.

The Update Space

Upcoming Sightings & Shenanigans

NERCOMP: Thought Partner Program: Navigating a Career in Higher Education. Virtual. Monday, June 2, 9, and 16, 2025 from 3pm-4pm (ET).

EDUCAUSE Online Program: Teaching with AI. Virtual. Facilitating sessions: June 23–July 3, 2025

Teaching Professor Online Conference: Ready, Set, Teach. Virtual. July 22-24, 2025.

Recently Recorded Panels, Talks, & Publications

“In the Room Where It Happens: Generative AI Policy Creation in Higher Education” co-authored with Esther Brandon, Dana Gavin and Allison Papini. EDUCAUSE Review (May 2025)

“Does AI have a copyright problem?” in LSE Impact Blog (May 2025).

“Growing Orchids Amid Dandelions” in Inside Higher Ed, co-authored with JT Torres & Deborah Kronenberg (April 2025).

Bristol Community College Professional Day. My talk on “DestAIbilizing or EnAIbling?“ is available to watch (February 2025).

OE Week Live! March 5 Open Exchange on AI with Jonathan Poritz (Independent Consultant in Open Education), Amy Collier and Tom Woodward (Middlebury College), Alegria Ribadeneira (Colorado State University - Pueblo) & Liza Long (College of Western Idaho)

Reclaim Hosting TV: Technology & Society: Generative AI with Autumm Caines

2024 Open Education Conference Recording (recently posted from October 2024): Openness As Attitude, Vulnerability as Practice: Finding Our Way With GenAI Maha Bali & Anna Mills

AI Policy Resources

AI Syllabi Policy Repository: 165+ policies (always looking for more- submit your AI syllabus policy here)

AI Institutional Policy Repository: 17 policies (always looking for more- submit your AI syllabus policy here)

AI+Edu=Simplified by Lance Eaton is licensed under Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International

Thank you for this thoughtful exploration of AI's role in education, Lance. Your point about the gap between technology integration promises and actual learning outcomes really resonates. The challenge you describe - faculty rebuilding that "rich, interconnected web" of learning outcomes, assessments, and materials after AI "scatters" everything - captures a recurring pattern in EdTech.

This recurring gap between EdTech innovation hype and true educational impact is something I've been thinking about extensively. There's a compelling analysis of this phenomenon at https://1000software.substack.com/p/technology-wont-save-schools that argues technology alone can't address the systemic challenges in education without fundamental changes to how we approach teaching and learning.

Your emphasis on "challenge, complexity, and connection" as foundations for skill development (drawing from Beane's work) seems particularly relevant here. I'm curious: when you work with faculty on AI integration, how do you help them distinguish between AI applications that genuinely support these foundational elements versus those that might inadvertently undermine them? What evidence of impact do you look for to know whether an AI-enhanced approach is truly serving learning versus just appearing innovative?

This piece absolutely hit the mark. Your framing of GenAI not as a replacement but as a catalyst for rethinking assessment resonated deeply. I’ve been working on scaffolding models that integrate structured content mapping, spiral learning, and AI-powered feedback loops and your point about aligning assessment with process, not just product, is critical.

I particularly appreciated the emphasis on authentic learning and the reminder that innovation should serve pedagogy: not just novelty.

One area I’d add to the conversation is the foundational role that skills like cursive handwriting can play in supporting the orthographic loop. -the cognitive process linking visual perception, motor coordination, and memory consolidation.

There’s compelling research suggesting that even in AI-supported models, preserving these practices strengthens neural pathways for reading fluency and long-term retention. Cursive handwriting: https://extension.ucr.edu/features/cursivewriting

While we may disagree on the fate of cursive, your piece strengthens my conviction that GenAI’s highest use isn’t automation: it’s alignment. I’m eager to keep exploring how GenAI partnerships can reshape what’s possible. -whether typed, printed, or (gasp) scrawled in Helvetica.

———————-

Note: The recommendation to explore your substack and the link to: AI + Education = Simplified came from my own GenAI partnership, with ELIOT (Emergent Learning for Observation and Thought).